Yesterday, Dr Manz and I went to Lexington, Kentucky to attend the memorial service for Teague Curless. It was good to gather with Teague’s friends and family so that we could talk about him and remember him, and share our aching hearts with each other.

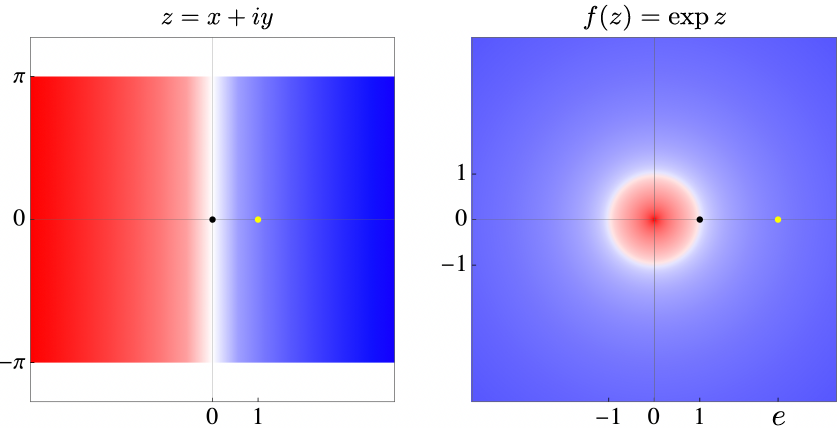

Teague’s family incorporated a lot of physics into the memorial service, including a beautiful discussion of energy conservation, reminding us that the total energy in the universe has been fixed since its creation, although that energy changes forms. The energy that was Teague is now in different forms, but no less real. They also read from a lovely commentary by Aaron Freeman about having a physicist speak at your funeral. These lines really struck me:

You want a physicist to speak at your funeral. You want the physicist to talk to your grieving family about the conservation of energy, so they will understand that your energy has not died…. You want your mother to know that all your energy, every vibration, every BTU of heat, every wave of every particle that was her beloved child remains with her in this world…

[You want the physicist to tell your family] that all the photons that ever bounced off your face, all the particles whose paths were interrupted by your smile, by the touch of your hair, hundreds of trillions of particles, have raced off like children, their ways forever changed by you.

I know it’s very hard for many of us this Monday, remembering that last Monday, Teague was getting settled on campus and preparing for his senior year. Things can change so quickly.

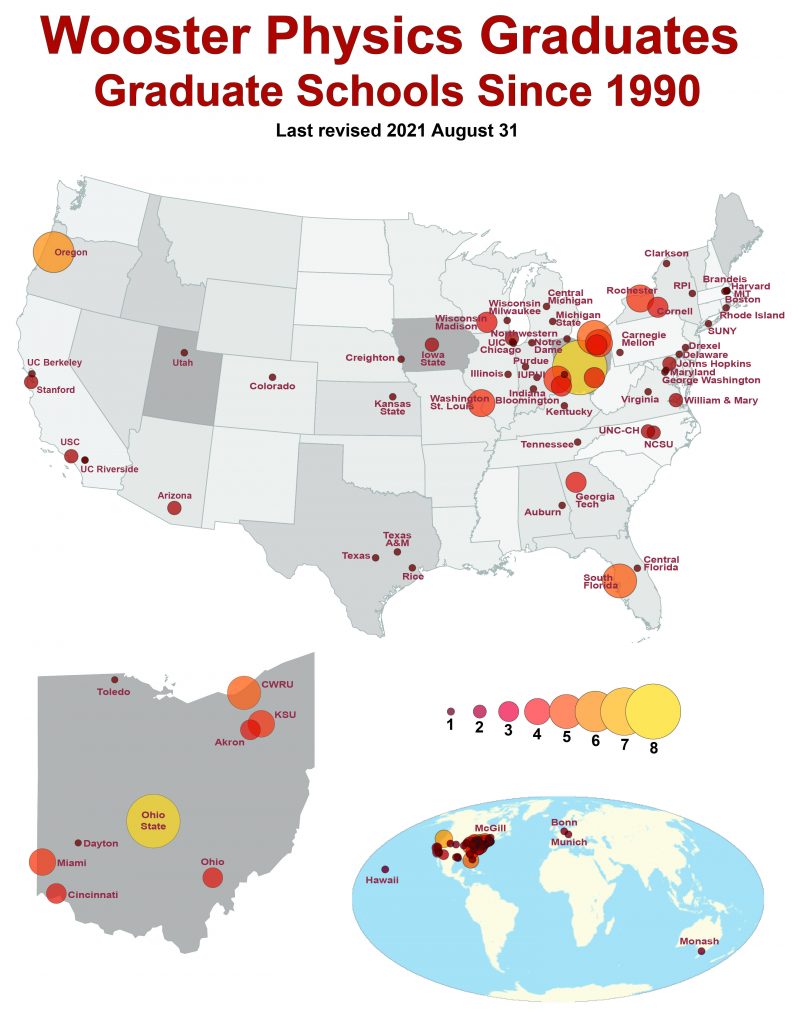

For me, the best part of my job is the relationships that I develop with the students. It’s a privilege to get to know you all as you grow and change so much from your first year to your fourth, and to keep in touch as you go out from Wooster and change the world in big ways and small. Thank you for the hugs and calls and emails this week — I am so grateful for all the ways that our community draws together to support one another in tough times like these.

Thanks, Mark! I enjoy reading your posts as well.