I knew when I posted the Day 1 update from the March Meeting that it would be pretty hard to keep up daily updates, and I was right!

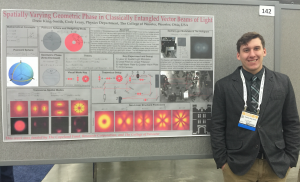

The students arrived on Tuesday morning, and Drew did a great job with his poster at the Tuesday afternoon poster session.

We all had dinner together at Amicci’s in Little Italy which was amazing. Elliot Wainwright ’15 who is now at Johns Hopkins had recommended it and was able to join us for dinner.

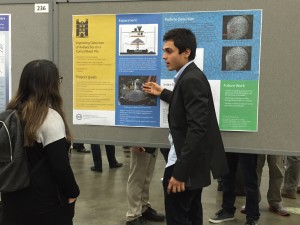

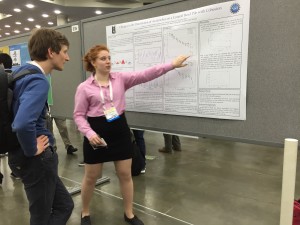

Day 3 – starting to get a little harder to get to those first sessions of the morning at 8 am! Avi and Justine had adjacent posters in the noon poster session and got lots of good traffic and had good conversations.

It was also a beautiful sunny day for the first time, and people were absolutely clustered enjoying the day down by the inner harbor.

In the evening, I ran into Justine at the Diversity Networking Reception. Before I bumped into her, she had been talking to another attendee who was a postdoc at Johns Hopkins. As I arrived, he asked her GPA and gave her his card and pretty much offered her a summer research job. That’s effective networking!

The evening ended with the Rock-n-Roll Physics Sing-a-long, which was hilarious. Geeky? Yes, but in a fabulous way. And, the band was really good!

Thanks, Mark! I enjoy reading your posts as well.